Museum Exhibits - Boomtown

Boomtown

"The growth of Chicago in population and wealth has been truly astonishing. A few years ago she was an inconsiderable village, and is now among the most populous cities in the Union...Her rapid progress ceases to be a matter of surprise, when we consider the advantages of her natural position, the number and extent of her public improvements, and the energy and enterprize [sic] of her citizens. She has a good harbor and a vast and increasing trade..."

-John Lewis Peyton, 1855

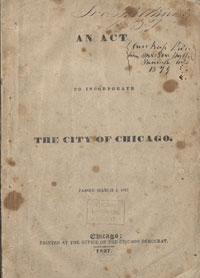

Incorporation papers, 1837

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Once a frontier town of soldiers and settlers, the fast-paced Chicago incorporated in 1837. Westward expansion placed the city at the literal crossroads of America. And the quest to build the Illinois & Michigan Canal--connecting the Chicago and Mississippi rivers--was becoming a reality.

The 1830s saw a canal workforce trickle into the city as land speculators, investors, and shipping merchants made a land grab. By the 1850s, boarding houses, lumber mills, brickyards, and wharves lined the Main Stem, which was often packed with so many ships that a person might cross the river on ship decks. A meat empire grew along the South Branch, and farms and homesteads peppered the marshy forks of the North Branch.

Artist's Rendering of Chicago, 1864

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Chicago Harbor

"Chicago is the only place where twenty vessels can be loaded or unloaded, or find shelter in a storm. A glance at the map, then, will show that it is the only accessible port--and hence the commercial centre--of a vast territory, measuring thousands of square miles of the richest agricultural county in the world."

-"Chicago in 1856", Putnam's Monthly Magazine

Chicago Harbor, 1854

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Making the River Work

Chicago's success was in its waterways, and the first order of business was to increase the harbor capacity by changing its shape.

The river turned south near Fort Dearborn and emptied into the lake at the present-day Art Institute. East of the river, a sandbar extended into the lake and caused problems for ships navigating the harbor.

Map of Chicago, 1830

The original mouth of the Chicago River meandered to Lake Michigan

In the early 1800s, soldiers, engineers, and sailors repeatedly dredged a channel though the sandbar, only to see it build up again. In 1837, the U.S. government funded a permanent channel and two piers that blocked lake winds and currents. The Chicago River had a new mouth.

Drawing of Chicago River, 1831

Wau Bun

Courtesy of Joni Marin

In the mid-1800s, the city made other changes to the Main Stem to accommodate shipping. These projects included dredging, widening, deepening, and building wharves, piers, and movable bridges.

Map of Chicago, 1839

Engineering plans for straightening the harbor.

Courtesy of Chicago Public Library

The Illinois & Michigan Canal

As canoes made way to tall ships and barges, the portage between the Chicago and Des Plaines rivers was no longer practical. Although Joliet's words indicate ease, building a canal to connect the two rivers was an engineering challenge.

The Illinois & Michigan Canal took twelve years to build (1836-1848) and cost $6,463,853. The elevation dropped by more than 140 feet over its ninety-six mile length. Fifteen locks controlled the water flow from five pumping stations and five aqueducts. The canal's opening transformed the little town of Chicago and its little river into one of the nation's transportation hubs.

Sales Certificate, 1830

A combination of land grants, state and federal funds, and loans covered the cost of building the canal.

Courtesy of Illinois State Archives

A trip through the I & M Canal took seventeen to twenty-four hours by mule or horse-drawn barge. For decades, the I & M Canal was busy, until 1900 when river traffic began to use the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal as its primary waterway.

I & M Canal Lady Lock Tender at Channahon, Late 1800s

Courtesy of John Lamb: Lewis University

I & M Canal Barge, ca. 1870

Courtesy of John Lamb: Lewis University

Ship Log

With the opening of the I & M Canal, Chicago became the nation's largest inland port. By 1880, it was the busiest port in the United States.

I & M Canal Working Conditions

I & M Canal working conditions were horrible, and men were paid $1 for a sixteen hour day, plus an allocation of whiskey.

"Laboring from day to day in low lands and stagnant water, human life has proved to be very short. Out of 1,500 laboring men employed on the canal, 1,000 died during this past year of over-exertion and the diseases incident to the climate, fever and ague and bilious water."

-Boston Pilot, 1839

Canal workers were paid in company-issued scrip.

Courtesy of Friends of the Chicago River

Factories and Farms

The new I & M Canal meant more river traffic, and the downtown riverbanks were now wharves, moorings, and turnabouts. Marble mills, tanneries, lumberyards, distilleries, and grain elevators lined the Main Stem. On the South Branch, stockyards and butchers used the river as their personal garbage dump.

Important changes also happened along the North Branch where farmers manipulated the rich, but wet, soil. They placed tiles under the soil to direct water off their fields into ditches that flowed to the Chicago River. Suddenly, what was once a slough was now a big ditch, hastening water runoff and soil erosion. It also increased the flow of the North Branch (which increased flooding) and accelerated wetland habitat loss.

North Branch, ca. 1900

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Chicago Onion Farm, ca. 1900

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

Looking Down the River from the Clark Street Bridge, ca.1875

Bubbly Creek

"As the offal [animal carcasses] settled to the bottom it began to rot. Grease separated and rose to the surface. Bubbles of methane formed on the bed of the river and rose to the surface, which was coated with grease. Some of these bubbles were quite large and when they burst, a stink arose. There were many local names for this part of the river, most unprintable."

-Ed Lace, who grew up near Bubbly Creek in the 1930s and 1940s.

Man Standing on Bubbly Creek, 1902

Courtesy of Chicago History Museum

A Dying River

"There was of course no plumbing and only outdoor privies. Almost every home had a stable. The wells were polluted and the river itself was an unfit source of supply, for the rains washed street and barnyard filth into its waters, and...fouled the lake near its mouth."

-John Clayton, "How They Tinkered with a River"

In Chicago's earliest days, waste was dumped into the streets or shallow pits within the city, creating a muddy, smelly mess. As a remedy, ditches soon lined the streets, diverting water and waste into the river.

In 1851, Chicago established a municipal water system--the first in the country--to deal with sewage. In 1856, they launched a two-decade project to raise the level of the streets. The entire city was raised two to twelve feet from its original height to accommodate the city's new combined sewer, into which stormwater and sewage emptied.

This solution cleaned the streets, but sent waste into the river, which flowed into Lake Michigan--the city's source for drinking water.

Sewer Plan, 1855

Courtesy of Chicago Public Library

Sewer Plan, 1871

Courtesy of Newberry Library

Chicago Daily Tribune, April 18, 1890

“Chicago River was on fire last night. It

burned fiercely for more than fifteen minutes

and the flames from the murky ooze rising to

a height of fifty feet set fire to the Kinzie

street bridge and the Northwestern railroad

bridge and to the approaches to both bridges

and the docks between them.”

“From all of the manholes of the Kinzie

street sewer as far west as Desplaines street

black smoke came up into the street and fire

alarms were turned in by the police all along

the route of the sewer.”

Courtesy of the Chicago Tribune.

Friends of the Chicago River

"In less then 100 years, the Chicago area went from a small outpost to the hub of cross-continental trade. As the region flourished, the river suffered. Like urban rivers everywhere, the Chicago was straightened, rerouted, and polluted by the residue of growth.

Today, we and many others are working together to improve the health of the Chicago River. A healthy river and environment increases quality of life for people, attracts businesses and tourists, and provides natural ecosystem services such as flood reduction, erosion prevention, and food and shelter to support a diversity of wildlife, strengthening the region's prosperity."

-Friends of the Chicago River, established 1979